Amending the Historic Preservation Act

“Yes, historical appetite among Americans is unprecedented and large. Of course it is served, and will continue to be served, by plenty of junk food. Of that professional historians may be aware. Of the existence of the appetite for history they are not.”—John Lukas, The American Scholar, Winter 1998

There was a hearing about proposed amendments to the National Historic Preservation Act in the House Resources Committee’s National Parks Subcommittee yesterday, April 21, 2005, which has created considerable blow-back in the preservationist community. It seems that preservationists think the sub-committee is going to knock a few teeth out of the Act. Still others think that it disregards private property owners.

Spearheading the dialogue was one Peter Blackman of Louisa County, whom the National Park Service has taken to court in both a civil enforcement action and a criminal prosecution for “violations” in the Green Springs Historic District.

This particular district has been at the heart of the war between no-growthers and people who actually believe there really is a Constitution that protects their property rights. The fundamental and ostensible justification for creating the district - the purported reason for its existence - is that it exhibits a "continuum" of historical farmlands. (The same could be said about anyplace.) I guess that explains why there is a virtually useless unencumbered hunk of State land (bought and paid for with tax money) sitting in the middle of it.

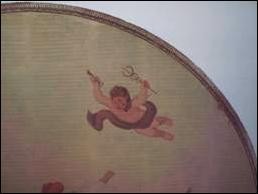

Sadly, well-intentioned people, who love history and historic things, when pressed, would rather destroy artifacts purely because of the National Historic Preservation Act. A perfect example is in the pictures below. I know what the significance of this ceiling is because I am an artist and I have researched it. It dates back at least to the 1920s and possibly further. It belongs to an organization that was established shortly after Virginia became a state. It contains symbols that date back to the Greeks. The folks who own it would rather hang sheet rock over it than subject themselves to the yoke of servitude to the National Trust and the National Park Service. The arrogance and oppressiveness of some of these agencies and their cronies undermines the ostensible intent of the Act. When ordinary people who are entitled to benefit from the Act (because they have built, bought and paid for it) uncover a relic, they say, “M’gawd, kill it before someone sees it!” They’re freedom is worth more to them than their heritage. The irony of it all is that these relics were designed to remind us of our heritage of freedom, and the sacrifices that were made for it.

Subcommittee chairman, Rep. Devin Nunes (R-Calif.), said “a disturbing trend of abuse” has emerged where historic preservation is used to clobber private property owner. He didn’t think this was the original intent of the Act.

No self respecting preservationist's tool kit would be complete without the tactic of premeditated nomination; meaning if they target a property, the owner is not only irrelevant, but prey. Today, a conscientious anthropologist can readily collect examples of the oral tradition, "If I could find (or put) a bone there, I'd nominate it." in the hallways of any preservationist agency. If they can’t legitimately document historic significance, they’ll pick a bone anywhere and call it anything in order to get a property into the mill.

That brings to mind a dialogue that took place back when George Allen was running for Congress. In an effort to “build consensus,” then candidate Allen brought together key players from the preservationist camp and grassroots leaders from property rights organizations in a trailer on the grounds of Vint Hill Station in Prince William County. Why he chose that site for the confab remains a mystery. One can only surmise that it might have been to insulate the neighbors from the frivolities or to protect the guilty.

Among the property rights attendees were many of the contributors to an infamous pamphlet called US vs. NPS. They came from a multitude of places where Historic Preservation and the National Park Service had committed atrocities including Richmond Battlefield, Brandy Station Battlefield, Manassas Battlefield, and the site a National Park whose only claim to national significance is the displacement, kidnapping, and in some cases sterilization and colonization its former inhabitants, Shenandoah National Park.

On the other team was a former heavy hitter with the National Trust for Historic Preservation Katherine Gilliam, lawyers for various well-healed political contributors, and Katie Couric’s dear departed husband, Jay Monahan.

We all had an opportunity to say our piece. As could be expected, the discussion heated up and one of the preservationists blurted out, “If I could find a bone on that property, you bet I’d nominate it!” Everyone in the room, including the preservationists recoiled. There was a dead silence. OOPS! It was like winning the lottery. Everything we had hoped and prayed for had just happened—they admitted it. They admitted abusing the Act to regulate neighboring properties. The kicker though, was this; and I will quote him, whether he has passed away or not, a lawyer announced to me that the Bill of Rights guaranteed me “Due process or just compensation—not due process and compensation.” This audacity was unfathomable, even for me, and the rest is history.

That was in 1992, shortly after we unveiled US vs. NPS.

One parting anecdote: While conducting research for US vs. NPS, I had the honor of interviewing Hugh Miller, the SHPO (State Historic Preservation Officer), and former NPS employee. He cordially invited us into his office and offered us seats. Mine was a Louis Quinze parlor chair, or some such. When I sat in it, a popped spring ejected me, giving rise…to a question. “Mr. Miller,” I asked, “what (pray tell) are the criteria for designating a property historic?” He glanced at me rising out of my chair, and in as genteel a manner as I’ve ever heard, he said, “Well, first of all, there has to be a certain sense of place.” Did he mean a sense of any place? I reckon that was something like, "a certain je ne sais quoi."

I congratulate Congressman Nunes for his efforts to protect the rights of property owners. I have difficulty comprehending why anyone would want to do otherwise.